| previous | 8 November 2006 | next

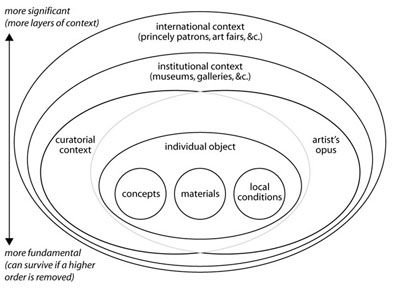

I ran into Tyler on Monday morning and we chatted briefly about The Uncertainty of Objects and Ideas at the Hirshhorn. Later, in a fit of delerium [I have a lingering cold that's really punishing me] I elaborated in a long-ish email, complete with Haliburton-style PowerPoint info-graphic. I've been mulling over our conversation today. I'm sure I sounded glib, but I've been really thinking it through and stand by my position that the show is worth seeing because of the strength of the individual pieces, regardless of curatorial stance [or lack thereof.] As a practitioner, my primary concern is whether or not the work can inform my process. A general viewer should be looking at individual pieces to see if they pose worthwhile questions. [Hence the strength of the idea of 'uncertainty.' Work that makes assertions, rather than poses questions, is in my mind either illustration, at it's best, or propaganda, at it's worst.] So, while curatorial and institutional context is important, it remains secondary to the individual pieces. To dismiss the work because of the context is in my mind akin to writing off a dissident intellectual who happens to live in a fascist state. For example: the Richter show was painfully crowded in the last couple of rooms. But regardless of that, I looked at each piece and extrapolated my own context. Besides, not every show can be Sugimoto. The proof of the fundamental nature of the work lies in the fact that if you take away the individual pieces, the institutions will go away; whereas, if you take away museums, the art goes on. Yes, curators, institutions, and 'international discourse' add layers of context, meaning and significance; however I think [for the moment at least] that the added significance gives diminishing returns as one goes farther up the hierarchy.

Regarding whether or not there is coherence to the show: I think there is - at a gut level the show made sense to me. But the brochure doesn't do a very good job of exposing what that might be [I haven't been to the gallery talks, though, nor did I read the wall texts.] In general, Anne Ellegood directs the viewer to consider questions of materials and relationships to art history. Personally, I think those questions are just art looking at itself, rather than at relationships to a broader world. When she goes on to the artists individually, she suggests that they each ask questions in various domains, but doesn't give *explicit* examples of questions. I'm sure the argument would be "that won't fit in a trifold brochure," but I think that's an excuse for not hiring a good copywriter/editor who can economically bring these questions into relief. Ellegood's last word on the matter:

Uh, yeah. And...? Maybe my ability to see has expanded, but what am I looking at? Now where I think she starts to propose a real thesis [at least one that I can get behind] is in the comments on two of the artists:

I think that the representation of networks, models and processes is the real subject that links most of the pieces, including those in the Collection in Context rooms. And there are plenty of contemporaries for whom these themes are subject or process: Tara Donovan, Tim Hawkinson, and Mark Lombardi are a few. [Lombardi in particular demonstrates explicitly what's at stake in a world that is much, much larger than a discussion of aesthetics and art history.] I think these representations are more than fashion or fad. Prior to the 20th century much art fell into landscape, portrait, or still life - in all cases centered on an individual person or event [the one obvious type that doesn't fit are the religious montages, like the doors of the Baptistry in Florence, favoring composition over linear time.] But roughly concurrent with socialism and relativity, Eisenstien, Schwitters and Joyce appear. None of them may have been the absolute first to decentralize the protagonist, but certainly they were the boldest exemplars of the transition. So what's going on now may be a hallmark of our time. Perhaps a new humanism is emerging. The question a general audience might ask is: Are networks - particularly the conscious mind [not an individual, but the very property of consciousness] - the new center around which the universe revolves? |